I have a longstanding interest in the architecture of urban environments. “The New Deal” grew out of my research into Logan Fontenelle, a signature housing project of the New Deal. My investigation was shaped by my own history as a child of parents who arrived in the United States as refugees from Latvia and Lithuania, part of a long history of uprooted peoples whose idea of “home” is contingent, in flux, without permanent definition and undermined by political agendas beyond their control. My parents spent years in displaced-persons camps in Germany before they were allowed to enter the United States. Their relatives who did not make it to the West lived through Soviet domination and its dramatic effect on their built environment: cultural buildings repurposed into warehouses, churches demolished, town centers allowed to decay. Cheap Soviet construction lacked insulation and adequate plumbing and heating. Visiting my relatives, I have seen firsthand the impact of politics on the architecture of urban housing, and on the lives of its residents.

American public housing took its lead from progressive social housing in Western Europe. Fearing that architects with no experience designing public housing would fail, New Deal administrators widely distributed detailed European plans as models. But on American soil, an architecture whose roots lay in a utopian ideal of improving humanity through clean design mutated into the embodiment of social hierarchy and non-architecture. Caps on spending led to cheaply manufactured complexes that eerily resembled their Soviet counterparts, earning them the disparaging assessment “Leningrad Formalism.”

Although newspapers touted complexes like Logan Fontenelle as the future of housing, the reality was not so rosy. Initially open to both white and African-American residents, it was only supposed to provide housing until they could earn enough to move out and move up. However, race-restrictive covenants elsewhere in the city meant that while white residents could move easily, African-Americans remained trapped.

Over the decades, life in the complex became violent, earning it the nickname “Little Vietnam.” A civil lawsuit over the government’s refusal to house low-income residents in other parts of Omaha led to the demolition of Logan Fontenelle in the early ‘90s, and the relocation of all its residents. Today, the site is a park and a pristine development of single-family homes. Nothing remains of a history that began with hope and high ideals and ended in tumult, demolition, and failure.

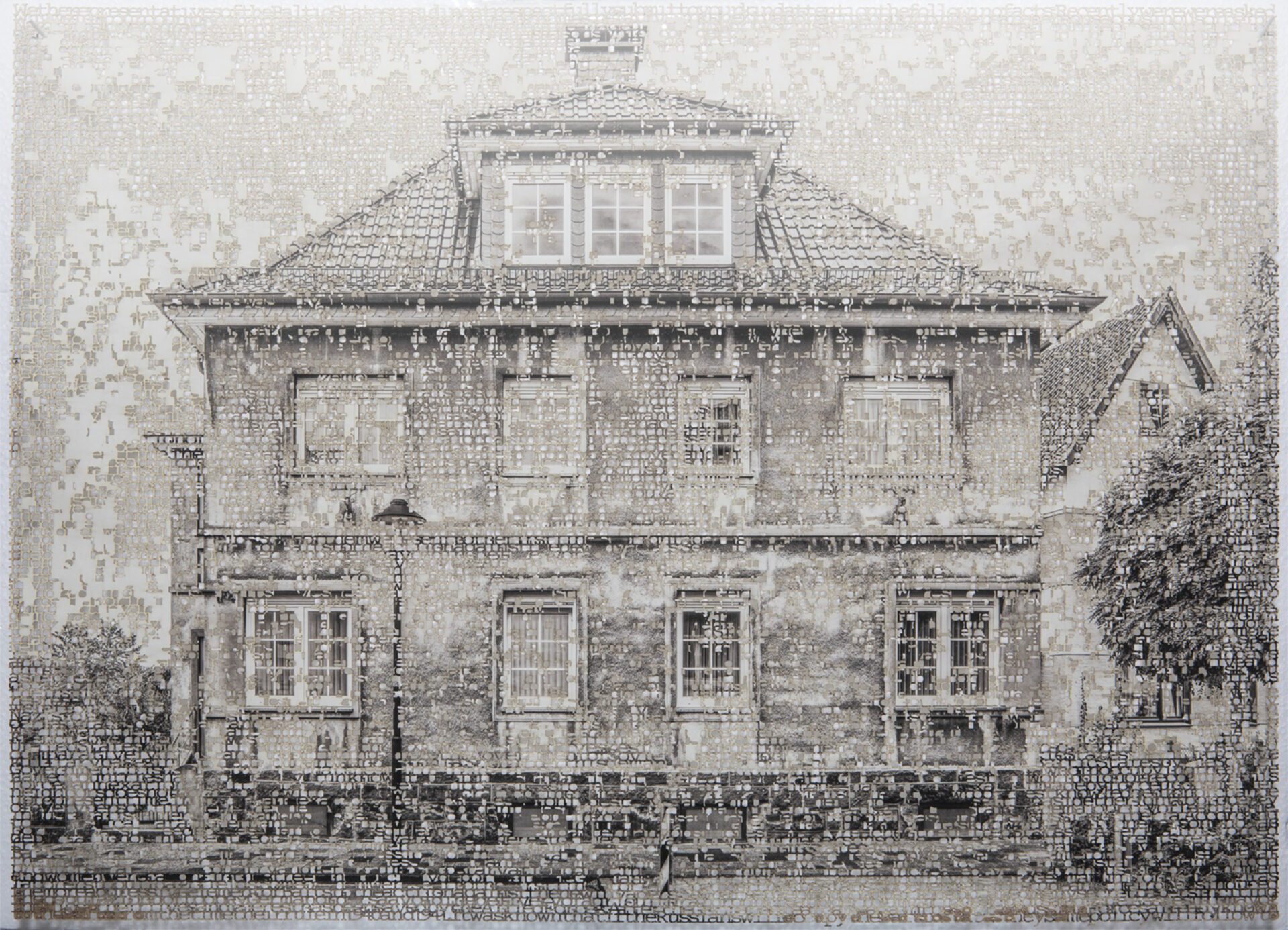

Across the country, public housing like Logan Fontenelle was by design almost invisible: sited on the cheapest available land, with featureless facades that virtually disappear into the surrounding concrete. To make the forgotten complex visible, I combined the original architectural plans with my photographs of the current housing development, using the forms of the past to shape the images of the present. Deliberate erasure is central to the history of public housing, so I cut into the architectural renderings, removing passageways, rooms, interiors, stairways. Yet each cut is hand-lined with gold leaf, as a trace of the architectural history of idealism that underlay the New Deal.